The central issue in the battle of public employee unions versus the people of Wisconsin, and the many looming similar confrontations elsewhere, is about the wisdom of having public employee unions in the first place. I searched for a discussion of the issue not colored by the politics, partisanship, and personalities of the current strife and found one in a long study published in the fall, 2010, issue of National Affairs, the intellectual journal. It was written by Daniel DiSalvo, assistant professor of political science at the City College of New York. Some excerpts:

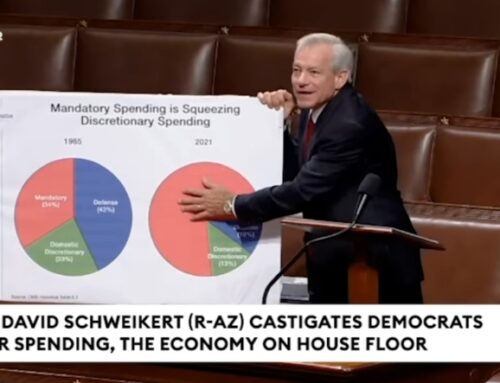

The cost of public-sector pay and benefits (which in many cases far exceed what comparable workers earn in the private sector), combined with hundreds of billions of dollars in unfunded pension liabilities for retired government workers, are weighing down state and city budgets. And staggering as these burdens seem now, they are actually poised to grow exponentially in the years ahead. If policymakers fail to rein in this growth, a fiscal crack-up will be the inevitable result….

As the Wall Street Journal put it recently, public-sector unions “may be the single biggest problem…for the U.S. economy and small-d democratic governance….”

To tolerate or recognize any combination of civil service employees of the government as a labor organization or union is not only incompatible with the spirit of democracy, but inconsistent with every principle upon which our government is founded. Nothing is more dangerous to public welfare than to admit that hired servants of the State can dictate to the government the hours, the wages and conditions under which they will carry on essential services vital to the welfare, safety, and security of the citizen. To admit as true that government employees have power to halt or check the functions of government unless their demands are satisfied, is to transfer to them all legislative, executive and judicial power. Nothing would be more ridiculous….

Taken together, the intrinsic advantages that public-sector unions enjoy over private-sector advocacy groups (including private-sector unions) have given organized government laborers enormous power over government at the local, state, and federal levels; to shape public finances and fiscal policy; and to influence the very spirit of our democracy. The results, unfortunately, have not always been pretty….

Public-sector unions thus distort the labor market, weaken public finances, and diminish the responsiveness of government and the quality of public services. Many of the concerns that initially led policymakers to oppose collective bargaining by government employees have, over the years, been vindicated.

Commentary sparked by the current unrest in the Midwest is also enlightening. Political analyst Jonah Goldberg wrote in a recent column:

Private-sector unions fight with management over an equitable distribution of profits. Government unions negotiate with friendly politicians over taxpayer money, putting the public interest at odds with union interests, and, as we’ve seen in states such as California and Wisconsin, exploding the cost of government. California’s pension costs soared 2,000 percent in a decade thanks to the unions.

The labor-politician negotiations can’t be fair when the unions can put so much money into campaign spending. Victor Gotbaum, a leader in the New York City chapter of AFSCME, summed up the problem in 1975 when he boasted, “We have the ability, in a sense, to elect our own boss.”

This is why FDR believed that “the process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service,” and why even George Meany, the first head of the AFL-CIO, held that it was “impossible to bargain collectively with the government.”

As it turns out, it’s not impossible; it’s just terribly unwise. It creates a dysfunctional system where for some, growing government becomes its own reward.

Charles Krauthammer, the brilliant political savant, said in his Washington Post column:

(Wisconsin Governor) Walker understands that a one-time giveback means little. The state’s financial straits—a $3.6 billion budget shortfall over the next two years—did not come out of nowhere. They came largely from a half-century-long power imbalance between the unions and the politicians with whom they collectively bargain.

In the private sector, the capitalist knows that when he negotiates with the union, if he gives away the store, he loses his shirt. In the public sector, the politicians who approve any deal have none of their own money at stake. On the contrary, the more favorably they dispose of union demands, the more likely they are to be the beneficiary of union largess in the next election. It’s the perfect cozy setup.

Political pundit Michael Barone wrote in a column:

(W)hat are the contributions that public employee unions make to our states and our citizens? Their incentives are to increase the cost of government and reduce down toward zero the accountability of public employees—both contrary to the interests of taxpaying citizens.

Michael A. Walsh, writing in the New York Post, said:

Let’s be clear about what’s at stake in Wisconsin…It’s not just about balancing the state budget, nor simply about collective bargaining. It’s not even about the future of the labor movement.

It’s about the future of the country and who is to be master—the voters or the “public servants.”

Peter Kirsanow, a former member of the National Labor Relations Board, wrote a short piece for the online National Review Corner arguing that many of the concerns driving private-sector bargaining are wholly absent from public-sector bargaining.

Andrew Biggs, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and Jason Richwine, senior policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation, wrote an instructive article in the Wall Street Journal showing that public employees in unionized states make much more in total compensation than their private-sector counterparts.

The daughter of friends of ours is active in the Madison protests and tellingly precedes each of her Facebook postings about the demonstrations with this picture not of anything like an American flag or clasped hands but a clenched fist, the symbol of raw power.